Argentina is embroiled in a scandal involving the Russian cult Ashram Shambala. The group’s founder and leader, Konstantin Rudnev, previously served 11 years in prison, and several Russian nationals affiliated with his movement are currently under investigation for human trafficking, forced labor, and the distribution of illegal narcotics. As a result, Russians in Argentina now face growing mistrust: landlords are refusing to rent them apartments, car rental companies are turning them away, and border checks have become more invasive. In Buenos Aires, police and immigration authorities have launched raids on Russian-owned businesses. One family, whose case was heard by an Argentine court on May 2, spent three days in detention simply because they were on the same flight as cult members.

Content

Fatherhood of convenience

From a Novosibirsk yoga circle to a cult with thousands of followers

How Ashram Shambala made life harder for Russian emigrants

Raiding the “Russians”

Fatherhood of convenience

The Argentine police opened an investigation into the Ashram Shambala cult after receiving a call from the Ramon Carrillo hospital in Bariloche, a Patagonian city located 1,500 kilometers from Buenos Aires. A doctor phoned police to report the suspicious behavior of a 22-year-old pregnant Russian woman who had come in for a checkup accompanied by two fellow Russians — both female. The other women answered every question on behalf of their pregnant compatriot, barely letting her speak. They bore no resemblance to interpreters and were not related to the patient.

The companions were detained after later bringing the young woman to the hospital to give birth — not because of their suspicious behavior, but because one of them attempted to alter the newborn’s registration documents. The companion attempted to write the surname “Rudnev” in the paternity section despite having been told by medical staff that this was not allowed unless the father was physically present at the hospital. According to investigators, the failed paternity claim was an attempt by the leader of Ashram Shambala to obtain legal status in Argentina, as a child born on Argentine soil is granted citizenship by birthright, and the parents, in turn, receive permanent residency and a fast-track path to citizenship. Even without citizenship, Argentine permanent residency allows visa-free travel to Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia.

On March 28, six days after the doctor's call, police arrested Konstantin Rudnev and six women traveling with him at the Bariloche airport. They were preparing to fly to Brazil via Buenos Aires. When the plan fell through, the cult leader attempted to slit his own throat. Cocaine was found in the group’s luggage.

Almost all of the suspects under investigation in Argentina for activities connected with the Ashram Shambala cult are Russian citizens. A total of 21 people have been already been charged: 19 women and two men, including the group’s 58-year-old founder, Konstantin Rudnev, who remains the only figure still in custody. He is being held in a maximum-security prison in the city of Rawson, in southern Argentina.

The others were released but had their passports confiscated. They are barred from leaving the country and are required to check in weekly at their local police stations. The criminal cases against them involve several charges, including: human trafficking (up to 8 years in prison), use of forced labor (up to 15 years), involvement in criminal activity, distribution of narcotics, and attempted document forgery.

Konstantin Rudnev, leader of the “Ashram Shambala” cult, after his arrest in Argentina

Argentine media reported that the detained women appeared emaciated, showing signs of chronic malnutrition and progressive hair loss. Police later made additional arrests at Jorge Newbery Airport in Buenos Aires and in the southern city of Neuquén. In Bariloche, authorities searched a country house where members of Ashram Shambala had been living. According to media reports, the Russians had rented the house with cash, covered the windows, and installed outdoor surveillance cameras. Inside, police found wigs, erotic lingerie, mattresses on the floor, dishes labeled with names, and locked boxes used to store food — as well as mushrooms believed to be hallucinogenic.

Argentine lawyer Leopoldo Murua represented Konstantin Rudnev and Tamara Saburova, who from March 30-April 7 was detained alongside him and is referred to in the Argentine press as his fiancée. During that time, the lawyer was unable to meet with either client, as the court had imposed a total communication ban on Rudnev and Saburova. “At first there were a lot of conflicting reports about the charges. What I know for certain is that the women were with Rudnev voluntarily. We also spoke with the relatives of the 22-year-old woman who gave birth. They said that Elena — if I’m not mistaken about her name — was also with him of her own free will,” Murua told The Insider.

Relatives say the woman who gave birth was with Rudnev of her own free will

Murua ceased representing Rudnev and Saburova after they changed lawyers. He believes that the release of 20 foreign nationals accused of serious criminal charges connected to their alleged activities as part of the cult may indicate that the authorities currently lack sufficient evidence to prove their guilt — particularly in relation to human trafficking and the use of forced labor.

According to Argentina’s immigration service, Konstantin Rudnev entered the country in October 2024, and the woman who gave birth in Bariloche arrived in January 2025. Russians can remain in Argentina as tourists without a visa for up to 90 days. Murua says neither Rudnev nor his fiancée Saburova had residency permits — meaning they were likely staying in the country illegally.

From a Novosibirsk yoga circle to a cult with thousands of followers

In Russia, Konstantin Rudnev served 11 years in prison. In 2013, a court in Novosibirsk found him guilty of rape, of establishing a religious organization that violated personal rights and freedoms, and of preparing to sell narcotics. He had been arrested in 2010, and heroin was found during a search. Testimony against him came from former members of the cult he created, Ashram Shambala. At the time, the cult operated in about twenty regions of Russia, including Moscow and St. Petersburg, and had representatives in Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Its following reportedly reached as many as 20,000 people.

The history of Ashram Shambala can be reconstructed in some detail thanks to two sources: the book Ashram Shambala: A Concentration Camp for God-Seekers, written by ex-member Natalya Koksharova; and a one-hour interview given to journalist Elena Pogrebizhskaya by former cult “priestess” Elena Zakharova, who spent more than 25 years by Rudnev’s side.

Zakharova and Rudnev met in the late 1980s in Novosibirsk at a time when Konstantin, a graduate of a technical college for mechanical engineering, was devouring any literature he could find on esotericism and Eastern practices. He performed exercise routines from the magazine Physical Culture and Sport and the newspaper Soviet Sport, eventually starting a yoga club. That’s how he attracted his first followers.

Konstantin Rudnev developed his teachings from books, magazine articles, and films. He devised a hierarchy, rituals, and a dress code. He skillfully capitalized on the Soviet-era hunger for the forbidden, the occult, and the mystical.

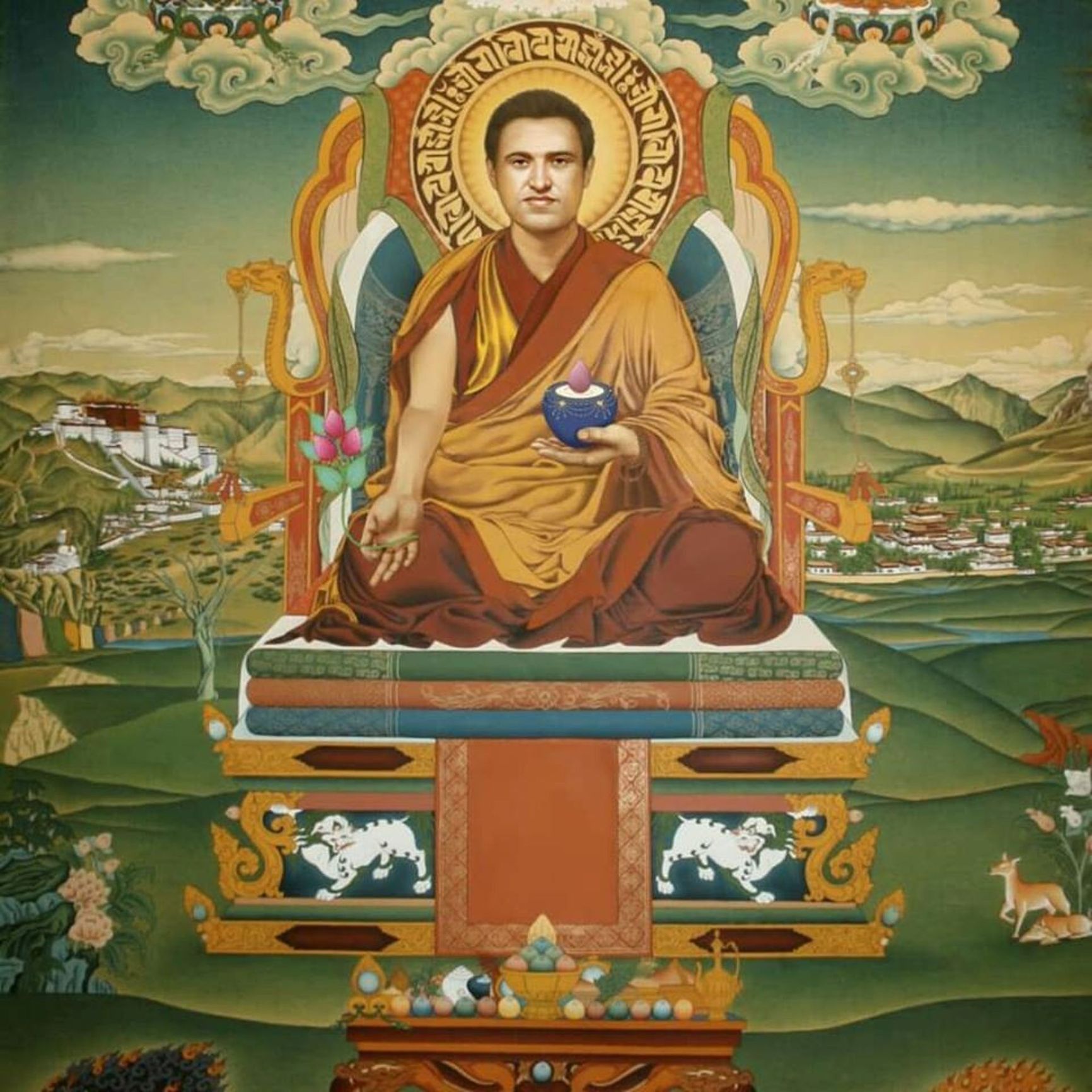

Stylized image of Konstantin Rudnev as an Eastern deity

At the end of 1991, using all the money brought in by the yoga circle, Rudnev and his followers placed an ad in the newspaper Soviet Sport titled “Spiritual Aikido. Occult Yoga.” The notice offered remote courses in “ancient Eastern techniques” and promised participants mastery of “astral combat,” “psy-energy defense methods,” clairvoyance, telepathy, hypnosis, teleportation, aura and photo diagnostics, and “spiritual healing.” Instruction was conducted by correspondence. One course cost 100 rubles — not cheap, considering the official average monthly salary in the USSR in 1991 was 548 rubles (and even that estimate was probably too high).

According to “priestess” Zakharova, that was the moment when interest in joining Ashram Shambala exploded. Off-site seminars lasting several days were initially held at sanatoriums and vacation homes near Novosibirsk, and they later expanded to a “nationwide scale.” A Russian investigation notes that Rudnev actively profited from publishing and selling booklets, audio cassettes, amulets, lectures, and instruction regarding various spiritual practices.

As of 2010, a “cleansing of energy channels” cost 1,500 rubles (about $47 at the time), while an “initiation ritual” went for 4,000 rubles (around $126). The operation was streamlined and highly organized. At off-site seminars, attendees were invited to get more deeply involved, and to live in the commune — at a cost, of course. People handed Rudnev money. They signed over property to him. They believed in healing, enlightenment, and the possibility of gaining access to some greater secret.

In 2010 prices, a “cleansing of energy channels” cost $47, and an “initiation ritual” cost $126

In her book, Natalya Koksharova recounts how Rudnev and the “mentors” explained the high prices of everything related to the “teaching”: “They claimed there was a law of energy exchange in the cosmos. Mentors transmit a vast amount of healing energy during the seminar, and in order to receive it — and not be destroyed — you must make an appropriate offering so the energy exchange can take place. Otherwise, you could get sick or even die.” By the early 2000s, the commune owned several apartments, two massive cottages near Novosibirsk, multiple expensive SUVs, and a whole fleet of motorcycles. Rudnev registered the property under the names of his “priestesses.”

Alongside the seminars, Konstantin Rudnev was also building his personal harem. At various times, it included between 20 and 30 women — first in an apartment, and later in a house. The “teacher” referred to himself as an “alien from Sirius,” and wherever he was living, that place was referred to as the “ashram.” A few close male followers, who mostly performed heavy labor for free, were called “elks,” while everyone outside the cult was labeled a “mouse.” Rudnev’s “priestesses” were expected to be thin, dye their hair black, wear heavy makeup, and dress in provocative clothing — all so as to resemble a Romani woman Rudnev had allegedly loved in his youth. Filming orgies and selling the videos also became part of the “religion.”

Rudnev’s “priestesses” were expected to be thin and dye their hair black to resemble a Romani woman the “teacher” had been in love with in his youth

Communication with relatives was discouraged and forbidden, as were getting involved in romantic relationships, starting a family, having children, or forming friendships. Disciples were required to constantly monitor one another and report everything to Rudnev. Cult members, who were housed in purchased or rented apartments, were kept as isolated as possible from the outside world. Their diet consisted mainly of rice and a few vegetables. They underwent prolonged fasts, never rested, trained intensively, and slept with the windows open regardless of the weather.

“From the malnutrition, constant stress, and physical strain, the girls stopped getting their periods. Rudnev didn’t have to spend money on pads or tampons — what a savings! We shared clothes, even underwear,” Koksharova writes in her book. If someone’s hair or teeth began falling out, the “teacher” explained it away as a sign that they were approaching the state in which they would feed solely on “divine energy.” Naturally, Konstantin Rudnev himself never fasted.

“Our clothes were shared, even underwear,” Koksharova recounts

Former “priestess” Elena Zakharova said in an interview that as early as the 1990s the so-called alien from Sirius had begun planning the cult’s expansion beyond the former USSR. Rudnev sent representatives to the United States and to South American countries, especially Brazil. The founder himself was arrested several times in Russia, but he usually managed to buy his way out. None of the cult’s members dared testify against him, and the cases were dropped.

In 2010, a Russian court sentenced Rudnev to 11 years in prison

However, after his arrest in 2010, Rudnev was sentenced to 11 years in prison. After being released in 2021, he obtained a passport and left Russia. News of the cult leader surfaced from Montenegro in the fall of 2024. Local police, responding to complaints from hotel guests about suspicious noise, discovered a cell of Ashram Shambala. It turned out the group’s members had been filming “ritual porn.” Rudnev vanished, and Montenegro declared him wanted. As is now known, in October 2024 the leader relocated to Argentina.

How Ashram Shambala made life harder for Russian emigrants

After the Russian army’s invasion of Ukraine, Argentina became one of the more popular destinations for Russians leaving the country — anti-war voices, LGBT refugees, freelancers, and thousands of pregnant Russian women arriving to give birth and obtain a local passport through their child. Argentine citizenship allows visa-free travel to 172 countries, including the European Union.

As a result, a sizable community of new Russian emigrants took shape in Argentina, especially in Buenos Aires. Most of them had never heard of Rudnev’s cult — until they felt the consequences of the arrest of the Ashram Shambala leader and his entourage.

Two of these were Anwar and Yulia, Russian citizens who have been living in Argentina for around a year and a half. The couple went hiking in Bariloche and were returning to Buenos Aires on the evening flight on March 28. According to Anwar, the check-in at the airport went smoothly, and boarding was the same. They were already on the plane when an airport employee suddenly rushed into the cabin. She began insistently asking one of the passengers in Spanish and English whether he was traveling alone or with someone. The man, judging by his reaction, did not understand her and responded in Russian. Using a translator on her phone, the employee managed to get the answer to her question: the passenger was traveling alone. The woman left the plane.

The flight was uneventful. Two hours later, they landed in Buenos Aires at Jorge Newbery Airport. There, a flight attendant asked over the loudspeaker for Konstantin Yakunin to approach the exit. This was the same man the airport employee had spoken to in Bariloche. Through the window, Anwar and Yulia saw that there were police officers outside the plane. The stewards asked passengers to have their documents ready and to proceed to the exit.

“We’re descending the stairs. The Argentinians show their ID cards and walk through. We take out our red passports. The police see them. They ask if we are Russians. And they immediately ask us to step aside,” Anwar recalls in an interview with The Insider.

The officers waited until the last passenger disembarked, then began asking Anwar and Yulia if they were traveling together, what they had been doing in Bariloche, and if they knew Konstantin Yakunin. The authorities then invited the couple to come with them to the police station located in the airport, where they were asked to place their mobile phones in a container. Until that moment, Anwar says, the police had been extremely friendly. He and his wife were sure that everything would end with a routine document check.

“We pulled out our red passports. The police saw them and immediately asked if we were Russians. Then they told us to step aside,” Anwar recalls

“We placed our phones in the container without thinking twice. In an instant, we were handcuffed. I started to panic, asking what was going on. They assured me it was just a formality,” Anwar explains, emphasizing that his Spanish was rather basic. Much of what the police said to him and Yulia was not entirely clear. From the moment of their arrest, the couple repeatedly requested to contact friends, relatives, a lawyer, or the Russian embassy. They also asked for a translator. “You’re not entitled to that. It’s an order from Bariloche. The case is with the prosecutor, and he prohibited it,” was the response.

Anwar was led to a small room, where he was asked to strip. They searched him, confiscated his belt and shoelaces, and then allowed him to get dressed. He managed to get one of the officers, who appeared to be of higher rank, to explain what they were suspected of. She typed “trata de personas” (human trafficking) into a translation app on her phone. Upon reading this, Anwar was stunned. “In Bariloche, it’s a cult. It’s protected by Russians. That’s why we detained you,” Anwar recalls the officer’s explanation. He tried to explain that he and Yulia didn’t even live in Bariloche and offered to show them photos from their trip.

Later, the couple was taken under guard to the airport’s basement and placed in separate cells. They were forbidden to communicate. When Anwar and Yulia continued to shout to each other, they were put back in handcuffs and threatened with complete separation. Anwar was placed in a cramped cell (four steps long, three steps wide), with a sink that had no water, a toilet without any partition, and a bed with an old, stained mattress. A man, covered by a jacket, was already asleep on the bed. It turned out to be Konstantin Yakunin.

“He slept like a dead man, despite all the noise. He looked about 50, short, thin, with a receding hairline. He had tattoos of rings on his fingers. He was dressed simply, just an ordinary Russian guy from the outskirts,” Anwar describes him. Later, Anwar understood the reason for his cellmate's complete calmness. When the two men managed to speak for a few minutes during the shift change of the police, Konstantin Yakunin told him that he had been to prison several times in Russia. His first sentence was in 1991, when he was incarcerated as a minor, and his last sentence was in 2007. Yakunin said he had come to Bariloche to visit a friend and had lived there for three months.

Later, three women, also suspected of being connected to the Ashram Shambala cult, were brought to the airport basement. According to Anwar, they appeared to be around 40-45 years old. All were slender, dressed in hiking clothes and trekking boots. The first one was named Alexandra. She was tall, with curly red hair — a Russian-speaking citizen of Mexico who had no trouble communicating with the police in Spanish. She looked subdued but entirely calm. The second was Oksana, a Russian woman. She seemed to be in emotional distress and was nervous about everything happening. The third was Paula, a Brazilian. Anwar recalls noticing her absolute composure and silence.

The six detainees spent nearly 24 hours in the airport’s basement cells. According to Anwar, during this time they were fed two meals — the kind usually served on airplanes — and for several hours their fingerprints were taken. They were strongly urged to sign some documents, the contents of which Anwar did not understand. In the end, he agreed to sign only the inventory of the confiscated personal belongings.

By morning on March 30, the six detainees were taken out of their cells and escorted to the airport's medical office. “Two police officers led me by the arms. In front and behind, there were two soldiers with automatic rifles as if I were Osama bin Laden. And four more on the sides. Eight people for one,” Anwar recalls. In the medical office, they asked about his health and measured his blood pressure. After that, without explanation, they put him in a police van and drove him to downtown Buenos Aires. A few hours later, the couple found themselves in solitary cells at Federal Detention Center No. 28. It was located just a few minutes' walk from the Supreme Court.

“It was a large, cold cell. There was no mattress. Two concrete bunks. It was very cold to sit and lie down. It was dirty. Huge cockroaches. There was feces and vomit on the walls. It smelled terrible. The light never went out. I walked in circles, squatted, did push-ups to keep warm. The guards came three times a day. They gave cold water and bread. They ignored any questions. My wife, as she later told me, was given a mattress and a blanket. At some point, I passed out on the concrete bunk. I caught a cold and got sick,” Anwar says. That’s how Sunday passed. Then Monday, March 31, came.

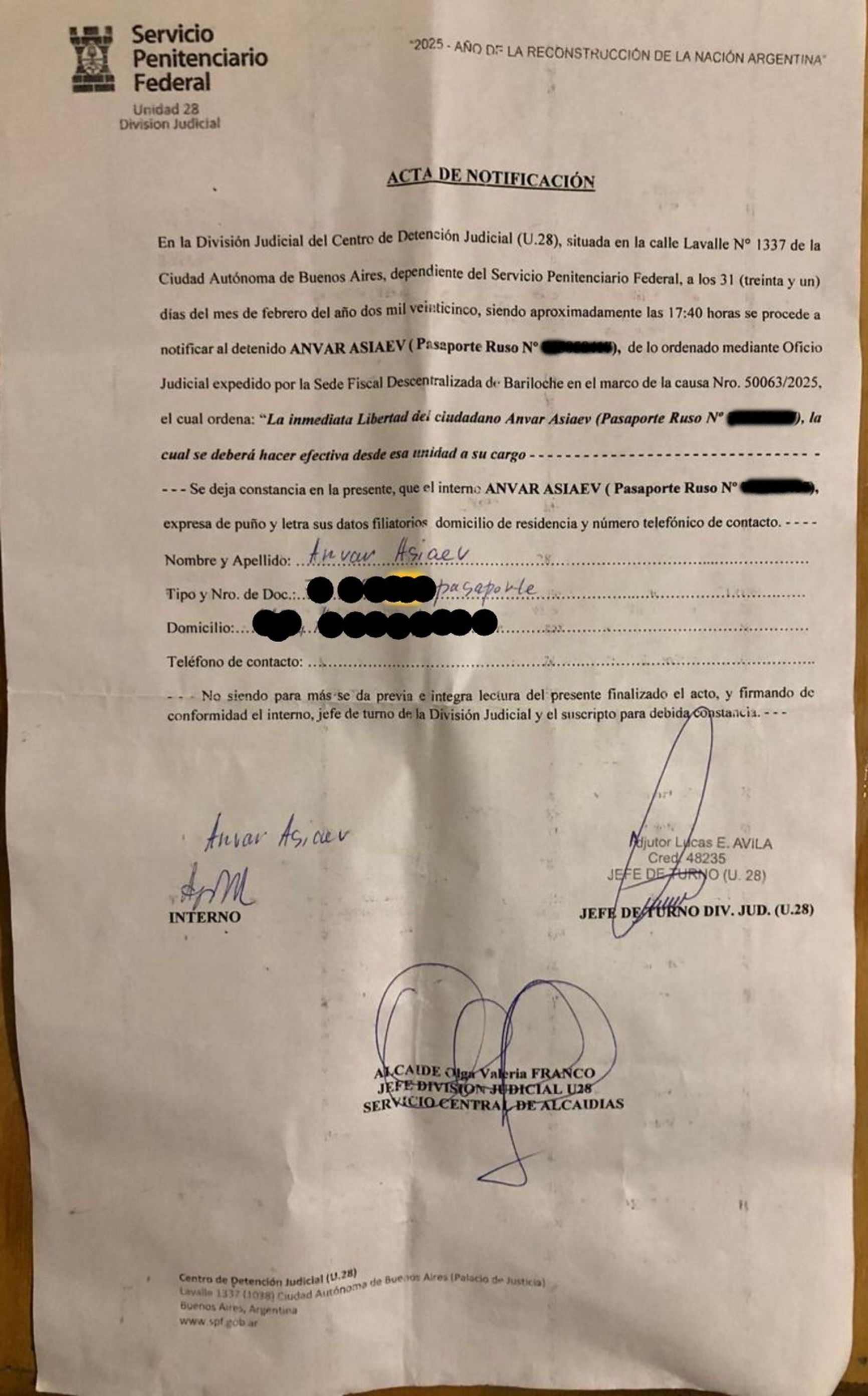

During the day, Anwar was taken to a small room with a screen. Via video link from Bariloche, an Argentine lawyer appointed by the state spoke to him — in Spanish, without a translator. She asked about Yakunin, whether Anwar practiced yoga, and whether he meditated. After that, he was returned to his cell, and later, he was brought back to the small room, where Yulia was also taken. The lawyer, via video link, announced that they would be released soon. The Insider has a copy of a document issued on March 31, 2025, by the Federal Penitentiary Service of Argentina. It concerns the “immediate release” of Russian citizen Anwar Asiev from custody.

Copy of the document on the immediate release of Russian citizen Anwar Asiev from custody

Anwar Asiev

The couple was released on March 31 at 19:20, having spent nearly three days behind bars. No charges were filed against them, but their phones, money, and confiscated documents were not returned. They were told to go to the airport and look for them there — a driver would even take them there for free after they presented the release statement. “We looked like homeless people — dirty, without shoelaces. Sick. We went to find the bus. We asked people. They recoiled from us. With great difficulty, we managed to get there,” Anwar recalls.

At the police station in the airport, they were not given anything back. Instead, they were told to find a lawyer and contact the consulate. It was a two-and-a-half-hour walk from the airport to their rented apartment. It turned out the landlord was already aware of the situation. The police had visited her and questioned her. Only at home, after opening the news, did the couple first read about Ashram Shambala, a group they had never heard of before. The next morning, they went to the Russian embassy. “A representative came out to us. He started speaking through his teeth. Like, ‘we know. But we can’t do anything. Not our jurisdiction. It’s a bit offensive, of course. But everything is okay now, right? They released you?’ He advised us to hire a lawyer.”

The state-appointed lawyer from Bariloche explained to Anwar and Yulia that, despite the absence of formal charges, investigators did not rule out their involvement in the case. Their passports, phones, and wallets had not been returned. Their case hearing was scheduled for May 2.

Raiding the “Russians”

The issue did not stop with Anwar and Yulia. Former Rudnev lawyer Leopoldo Murua told The Insider that his partner in Bariloche had already encountered several instances in April in which Russians were refused rental properties and vehicles solely because of their citizenship. Additionally, Murua said that after Rudnev’s arrest, he and other colleagues received a “cascade of calls,” as he described it, from Russians in Argentina who were subjected to extra checks and inspections while traveling around the country or crossing borders. In all these cases, the only reason for the scrutiny was their Russian citizenship.

For over a year, a monthly Russian-language festival called Aurora had been taking place in Buenos Aires, but on April 9, the organizers announced that they had been “forced to cancel the April 13 fair due to growing pressure on the Russian-speaking community in Argentina. This is linked to the recent events in Bariloche and the scandal surrounding the cult organized by Russian nationals.” In an interview with The Insider, Aurora organizers Anton and Pavel explained that they made the decision after several “Russian” businesses in Buenos Aires were inspected. The federal police and immigration services had already raided at least two premises frequented by Russians — the Gafarov SPA bathhouse and the Bucarest bar — checking the documents of both staff and visitors. As Anton and Pavel noted, Aurora could become another target for such raids.

The organizers did not want to risk inviting document checks of Russians who might still be in the process of legalizing their status in Argentina, or who could be challenging refusals of residence permits in court. Their fears were not misplaced. On April 24, a Russian-speaking kindergarten club in Buenos Aires reported that it had been subjected to a police visit.

Argentine law enforcement's focus on the “Russian” community in the country remains intense. The next round of inspections may well occur towards the end of May, when the court begins to review the cases of ordinary cult members. Or it could pick up again in mid-June, as Konstantin Rudnev’s detention was extended for an additional 60 days starting from April 11.